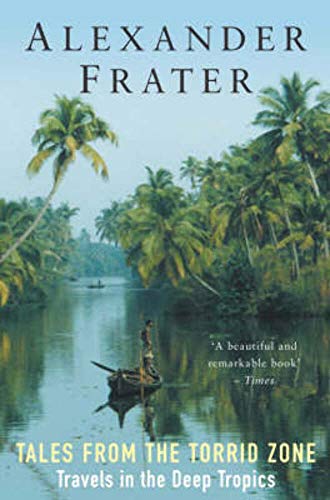

Articles liés à Tales from the Torrid Zone: Travels in the Deep Tropics

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBN

Extrait :

A Place Called Pandemonium

Some years ago I returned to my birthplace and found it had become a luxury holiday resort. Described in the brochures as “Iririki, Island of Elegance” and lying snugly in Port Vila’s blue harbour, its forty-four acres were crowned with flowering trees and contoured like a tall polychromic hat; you could walk the shadowy path around its brim in twenty minutes. It was a comfortable spot; when the mainland sweltered, Iririki usually got sea breezes and cooling showers. Once it had contained just two houses: our mission bungalow and—set in parklike grounds with a flagpole flying a bedspread-sized Union Jack—the palatial residence of the British Resident Commissioner. Now seventy-two air-conditioned accommodation units were strung across its northern end.

By the resident’s jetty a signpost read “Old Hospital Ruins.” Directed back half a century, I saw myself as the guests drifting over on parasails might see me: an ageing, perspiring, overweight man hurrying towards a jungly acre that looked like an abandoned archaeological site. Somewhere in there, among the creeper-strewn hillocks and slabs of mossy concrete, my father had delivered me with forceps; now I expected, if not a thunderclap, at least an acknowledgement, some audible sign.

That, however, only came at the check-in desk when a porter cried, “Welcome to the Champagne Resort!” and handed me a complimentary fruit punch. Drinking it, I realized the vaulted reception area, built from local hardwoods, stood on the site of our vegetable garden. Then, having spelled my name for the clerk, I told her about my links with the island. She went “Uh-huh,” and asked for my credit card. Handing me a key she said, “Enjoy your stay, Mr Fraser.” My unit overlooked a tiny, fan-shaped beach where I had learned to swim; two topless women lay sunning themselves on the spot where I once kept my canoe. Later, eating a Big Riki burger at the poolside restaurant, I was relieved to find the restaurant’s location held no associations at all.

My son turned up and said, “How do you feel? Have the squatters moved in?”

I felt pretty good, actually—indeed, oddly gratified that so many people seemed to be getting pleasure from the place. “What do you think?”

“It was probably nicer before.”

But John detested resorts of any description. He had arrived a couple of weeks earlier, a Royal London Hospital medical student out here to do his elective at his grandfather’s old hospital—today named Vila Base and re-established over on the mainland. Looking tired and preoccupied, he said a nine-year-old girl from Tanna had been admitted that morning with cerebral malaria. “Her parents tried a custom doctor, that didn’t work, so they brought her in: Western medicine, last resort, it happens all the time. A few hours earlier and we might have saved her.”

I watched my son pondering one of the diseases which my father, for much of his life, had fought so obsessively. That oddly jolting moment was interrupted by the arrival of Dr Makau Kalsakau, escorted to our table like a visiting head of state. Three waiters tussled to pull out his chair, a portly Australian manager hovered anxiously. Dr Makau, trained by my father and perhaps our oldest family friend, had promised us an Iririki island tour. A handsome, black-skinned pensioner with amused eyes and a wispy Assyrian beard, he held John’s hand and said, “You look like your grandaddy, there is a definite similarity. He was my teacher. And now you are working in our hospital! About this there is, uh, a kind of . . . what is the word?”

I had disappointed him by not going to medical school, but words were my business and now I was oddly eager for his approval. “Symmetry.”

“Hmm, yes.” (Symmetry would do.) “So what do you make of our new Iririki?”

“Not bad. But I’m still a bit confused.”

“Let us climb the hill. John, you should see what is up there. The tourists never go, they don’t know. And for you, Sandy, it will be more familiar.”

Dense undergrowth walled off our garden. But we found a way in, a dozen paces spanning fifty years and leading to a half-acre so still and shadowy I felt I had broken into my own childhood.

The place was running wild but evidence of our tenancy remained. The flowering trees my mother planted grew with a jungle exuberance, the grass was knee-high and the banyan that loomed so massively over our front veranda had acquired half a century’s extra girth and a further forty feet of elevation.

Our house, said Makau, had been demolished after we’d gone, whirled out to sea by the great 1948 hurricane. But the garden endured, and I knew its tangled boisterousness would have delighted my mother.

Beneath the banyan Makau paused. “Here Mummy built her school.” John raised an eyebrow at this nursery nomenclature, but among the old-timers hereabouts it was routine; to Makau I would be perennially juvenescent, an ageing toddler with a worrying weakness for cigars. I was touched to see the spot where the smol skul had stood. When the British and French refused to countenance any form of state education my mother took matters into her own hands. It proved so successful that later, a few yards away, she also built a teachers’ training college.

Our garden thus became a centre of academic excellence. The school produced—to the unease of both metropolitan governments—two streams of keen, bright kids. One entered the teachers’ training shack, the other headed down to the hospital where my father taught them to be doctors. That was how Makau, one of the first garden graduates, had learned his medicine. “All this bougainvillaea Mummy planted. She planted these frangipanis. You planted that orange tree. These hibiscus Daddy planted.”

I noted the absoluteness of the silence. Several dozen holidaymakers were making merry below, but the density of the bush excluded their voices. We clambered down forty broken steps to the razed Paton Memorial Hospital. This wilderness was Makau’s old alma mater. Sweeping aside a spinnaker-sized spider’s web he nodded towards a small depression carpeted with prickly sensitive plant. “Labour ward, you were born there.” We stumbled on through heavy scrub. By a young sandalwood tree he said, “Hospital front steps. At seven sharp every morning Daddy came down from the house wearing a tie and held a service for patients and staff. After that he did his rounds.” That startled me. The idea of a tie in this climate was one thing, officiating at morning prayers quite another. He had been a Presbyterian misinari dokta, Glasgow-born, ordained after finishing his MB BS, but I never thought of him formally facing a congregation, couldn’t equate that with the quiet, rather shy and private man I remembered. We toured the sites of the general wards, the path lab, the theatre and, set by the beach like an elegant little Edwardian boathouse, the shell of the mortuary. The evening sun made the wooded hills above Port Vila a landscape worked in silks. An outrigger canoe slid past, propelled by a woman in a crimson dress.

“Gud naet!” she called.

As we strolled along a coastal path the resort guests were abandoning the beach for Happy Hour. They glanced curiously at Makau; normally the only native Vanuatuans, or ni-Vanuatu, hereabouts were employees. We progressed through the lobby to the pool bar and the staff rushed to secure a table for us. Makau walked in as though he owned the place—which, in a sense, he did—and called for orange juices all round. His home island, Ifira, lay less than a quarter of a mile away, its eight hundred people long regarded as Vanuatu’s elite; a progressive, industrious, enterprising crowd, they flocked to my mother’s schools and, today, play a major role in the country’s affairs. Iririki belongs to Ifira, and it was a typically shrewd Ifira move to lease it to an Australian development company. Makau said, “In seventy-five years we get the island back—plus a top-quality international resort. They build it. We keep it.”

The guests, mostly well-heeled Australians in designer evening wear, began drifting in for cocktails, and as a band played island music I thought of my parents living quietly up on the hill, making do on their mission stipend, poor as church mice.

But there had been compensations and we were witnessing one now—a sunset so stunning that around the pool bar all tok tok ceased. The horizon was invaded by an unearthly lavender light which came spilling across the sky then fell into the harbour at our feet, empurpling the air and water, painting our faces with amaranth. Makau told John about Vila Base, built by the American navy in 1941 on the old Belleview Plantation. “It had one thousand beds and thirty-six doctors, all top people. Every day C47s flew up to Guadalcanal to bring the casualties. At Bauer Field forty ambulances would be waiting, hospital ships called all the time. I remember the Solace, painted white with a big red cross on the funnel. She used to sail at night, all lit up like a cruise boat. There were Jap subs everywhere, but . . .” He shrugged. “The old Paton Memorial nameplate is now at Vila Base. In reception.”

John nodded. “Yes, I know.” But he didn’t know that Makau had been its first post-independence superintendent. My father’s best student had succeeded him at the infinitely superior hospital he had long badgered the condominium government to build.

It was getting late. Makau rose. “Lookim yu!” he said.

See you later.

*

Vanuatu’s eighty islands, routinely rattled by earthquakes, ...

Revue de presse :

Some years ago I returned to my birthplace and found it had become a luxury holiday resort. Described in the brochures as “Iririki, Island of Elegance” and lying snugly in Port Vila’s blue harbour, its forty-four acres were crowned with flowering trees and contoured like a tall polychromic hat; you could walk the shadowy path around its brim in twenty minutes. It was a comfortable spot; when the mainland sweltered, Iririki usually got sea breezes and cooling showers. Once it had contained just two houses: our mission bungalow and—set in parklike grounds with a flagpole flying a bedspread-sized Union Jack—the palatial residence of the British Resident Commissioner. Now seventy-two air-conditioned accommodation units were strung across its northern end.

By the resident’s jetty a signpost read “Old Hospital Ruins.” Directed back half a century, I saw myself as the guests drifting over on parasails might see me: an ageing, perspiring, overweight man hurrying towards a jungly acre that looked like an abandoned archaeological site. Somewhere in there, among the creeper-strewn hillocks and slabs of mossy concrete, my father had delivered me with forceps; now I expected, if not a thunderclap, at least an acknowledgement, some audible sign.

That, however, only came at the check-in desk when a porter cried, “Welcome to the Champagne Resort!” and handed me a complimentary fruit punch. Drinking it, I realized the vaulted reception area, built from local hardwoods, stood on the site of our vegetable garden. Then, having spelled my name for the clerk, I told her about my links with the island. She went “Uh-huh,” and asked for my credit card. Handing me a key she said, “Enjoy your stay, Mr Fraser.” My unit overlooked a tiny, fan-shaped beach where I had learned to swim; two topless women lay sunning themselves on the spot where I once kept my canoe. Later, eating a Big Riki burger at the poolside restaurant, I was relieved to find the restaurant’s location held no associations at all.

My son turned up and said, “How do you feel? Have the squatters moved in?”

I felt pretty good, actually—indeed, oddly gratified that so many people seemed to be getting pleasure from the place. “What do you think?”

“It was probably nicer before.”

But John detested resorts of any description. He had arrived a couple of weeks earlier, a Royal London Hospital medical student out here to do his elective at his grandfather’s old hospital—today named Vila Base and re-established over on the mainland. Looking tired and preoccupied, he said a nine-year-old girl from Tanna had been admitted that morning with cerebral malaria. “Her parents tried a custom doctor, that didn’t work, so they brought her in: Western medicine, last resort, it happens all the time. A few hours earlier and we might have saved her.”

I watched my son pondering one of the diseases which my father, for much of his life, had fought so obsessively. That oddly jolting moment was interrupted by the arrival of Dr Makau Kalsakau, escorted to our table like a visiting head of state. Three waiters tussled to pull out his chair, a portly Australian manager hovered anxiously. Dr Makau, trained by my father and perhaps our oldest family friend, had promised us an Iririki island tour. A handsome, black-skinned pensioner with amused eyes and a wispy Assyrian beard, he held John’s hand and said, “You look like your grandaddy, there is a definite similarity. He was my teacher. And now you are working in our hospital! About this there is, uh, a kind of . . . what is the word?”

I had disappointed him by not going to medical school, but words were my business and now I was oddly eager for his approval. “Symmetry.”

“Hmm, yes.” (Symmetry would do.) “So what do you make of our new Iririki?”

“Not bad. But I’m still a bit confused.”

“Let us climb the hill. John, you should see what is up there. The tourists never go, they don’t know. And for you, Sandy, it will be more familiar.”

Dense undergrowth walled off our garden. But we found a way in, a dozen paces spanning fifty years and leading to a half-acre so still and shadowy I felt I had broken into my own childhood.

The place was running wild but evidence of our tenancy remained. The flowering trees my mother planted grew with a jungle exuberance, the grass was knee-high and the banyan that loomed so massively over our front veranda had acquired half a century’s extra girth and a further forty feet of elevation.

Our house, said Makau, had been demolished after we’d gone, whirled out to sea by the great 1948 hurricane. But the garden endured, and I knew its tangled boisterousness would have delighted my mother.

Beneath the banyan Makau paused. “Here Mummy built her school.” John raised an eyebrow at this nursery nomenclature, but among the old-timers hereabouts it was routine; to Makau I would be perennially juvenescent, an ageing toddler with a worrying weakness for cigars. I was touched to see the spot where the smol skul had stood. When the British and French refused to countenance any form of state education my mother took matters into her own hands. It proved so successful that later, a few yards away, she also built a teachers’ training college.

Our garden thus became a centre of academic excellence. The school produced—to the unease of both metropolitan governments—two streams of keen, bright kids. One entered the teachers’ training shack, the other headed down to the hospital where my father taught them to be doctors. That was how Makau, one of the first garden graduates, had learned his medicine. “All this bougainvillaea Mummy planted. She planted these frangipanis. You planted that orange tree. These hibiscus Daddy planted.”

I noted the absoluteness of the silence. Several dozen holidaymakers were making merry below, but the density of the bush excluded their voices. We clambered down forty broken steps to the razed Paton Memorial Hospital. This wilderness was Makau’s old alma mater. Sweeping aside a spinnaker-sized spider’s web he nodded towards a small depression carpeted with prickly sensitive plant. “Labour ward, you were born there.” We stumbled on through heavy scrub. By a young sandalwood tree he said, “Hospital front steps. At seven sharp every morning Daddy came down from the house wearing a tie and held a service for patients and staff. After that he did his rounds.” That startled me. The idea of a tie in this climate was one thing, officiating at morning prayers quite another. He had been a Presbyterian misinari dokta, Glasgow-born, ordained after finishing his MB BS, but I never thought of him formally facing a congregation, couldn’t equate that with the quiet, rather shy and private man I remembered. We toured the sites of the general wards, the path lab, the theatre and, set by the beach like an elegant little Edwardian boathouse, the shell of the mortuary. The evening sun made the wooded hills above Port Vila a landscape worked in silks. An outrigger canoe slid past, propelled by a woman in a crimson dress.

“Gud naet!” she called.

As we strolled along a coastal path the resort guests were abandoning the beach for Happy Hour. They glanced curiously at Makau; normally the only native Vanuatuans, or ni-Vanuatu, hereabouts were employees. We progressed through the lobby to the pool bar and the staff rushed to secure a table for us. Makau walked in as though he owned the place—which, in a sense, he did—and called for orange juices all round. His home island, Ifira, lay less than a quarter of a mile away, its eight hundred people long regarded as Vanuatu’s elite; a progressive, industrious, enterprising crowd, they flocked to my mother’s schools and, today, play a major role in the country’s affairs. Iririki belongs to Ifira, and it was a typically shrewd Ifira move to lease it to an Australian development company. Makau said, “In seventy-five years we get the island back—plus a top-quality international resort. They build it. We keep it.”

The guests, mostly well-heeled Australians in designer evening wear, began drifting in for cocktails, and as a band played island music I thought of my parents living quietly up on the hill, making do on their mission stipend, poor as church mice.

But there had been compensations and we were witnessing one now—a sunset so stunning that around the pool bar all tok tok ceased. The horizon was invaded by an unearthly lavender light which came spilling across the sky then fell into the harbour at our feet, empurpling the air and water, painting our faces with amaranth. Makau told John about Vila Base, built by the American navy in 1941 on the old Belleview Plantation. “It had one thousand beds and thirty-six doctors, all top people. Every day C47s flew up to Guadalcanal to bring the casualties. At Bauer Field forty ambulances would be waiting, hospital ships called all the time. I remember the Solace, painted white with a big red cross on the funnel. She used to sail at night, all lit up like a cruise boat. There were Jap subs everywhere, but . . .” He shrugged. “The old Paton Memorial nameplate is now at Vila Base. In reception.”

John nodded. “Yes, I know.” But he didn’t know that Makau had been its first post-independence superintendent. My father’s best student had succeeded him at the infinitely superior hospital he had long badgered the condominium government to build.

It was getting late. Makau rose. “Lookim yu!” he said.

See you later.

*

Vanuatu’s eighty islands, routinely rattled by earthquakes, ...

“Chancy, devastating weather is the bad news about the tropics. The good news is that the travel writer Alexander Frater has again been navigating the region, as he did so memorably in Chasing the Monsoon . . . Frater skips lightly among dozens of countries and several centuries . . . He is unfailingly jolly even when–especially when–faced with wretched food and sanitation . . . As in Proust’s epic, this is the story of how a child grew up to become the author of the savory book we are reading.”

–Richard B. Woodward, New York Times (Armchair Traveler)

“Ranging broadly over this vast area [of the tropics], Frater tells tall tales, gives lessons in history, politics, and economics, and recounts his personal adventures. This world is literally teeming with natural wonders, local characters, and wild stories . . . Entertaining.”

–Barbara Fisher, Boston Globe

“Frater’s thoughts and conversations reveal the torrid zone on a very personal level. The reader can almost feel the stifling wet heat . . . [A] beautifully written book.”

–Library Journal

“Tales from the Torrid Zone [has a] jagged edge of authenticity . . . Part memoir, part travel yarn, a hymn to the solar lands where people ‘wear their shadows like shoes’ . . . Frater adopts a tropical profusion of language to match his teeming subject, writing with gusto . . . He’s bracingly willing to take verbal as well as physical risks [but] some of the best things in the book are quieter, more lyrical moments . . . Wide-ranging . . . Impressive.”

–Christopher Benfey, The New York Times Book Review

“Part memoir, part travelogue, Tales From the Torrid Zone is a pleasing grab bag of a book, a jumble of funny encounters, strange sights, forgotten history and really bad food. Mr. Frater, a genial tour guide and a stylish writer, makes excellent company . . . [A] diverting tour of the earth’s hot zones.”

–William Grimes, The New York Times

“An outstanding memoir . . . Not everyone born and bred in the tropics likes tropical life. But just as church bells in the tropics have a unique resonance, so Frater himself has the human version of ‘tropical resonance.’ Everything about life in the tropics–food, diseases, insects, religion, rivers, language, drink, forestry, human sweat–is endlessly fascinating for him, reminding him of a story he heard traveling downstream from Mandalay, or filming in Mozambique, or riding a bus into Rarotonga. He finds the smallest details of tropical life so entertaining, he barely notices the attendant inconveniences. Thus he makes the insects eating his grandfather's book-selectively consuming its constituent parts, ‘the spine's sweet glue and crunchy muslin, biscuity strawboard covers, a confit of gold leaf licked from the titles’–sound like regular gourmands.”

–Publishers Weekly (starred)

–Richard B. Woodward, New York Times (Armchair Traveler)

“Ranging broadly over this vast area [of the tropics], Frater tells tall tales, gives lessons in history, politics, and economics, and recounts his personal adventures. This world is literally teeming with natural wonders, local characters, and wild stories . . . Entertaining.”

–Barbara Fisher, Boston Globe

“Frater’s thoughts and conversations reveal the torrid zone on a very personal level. The reader can almost feel the stifling wet heat . . . [A] beautifully written book.”

–Library Journal

“Tales from the Torrid Zone [has a] jagged edge of authenticity . . . Part memoir, part travel yarn, a hymn to the solar lands where people ‘wear their shadows like shoes’ . . . Frater adopts a tropical profusion of language to match his teeming subject, writing with gusto . . . He’s bracingly willing to take verbal as well as physical risks [but] some of the best things in the book are quieter, more lyrical moments . . . Wide-ranging . . . Impressive.”

–Christopher Benfey, The New York Times Book Review

“Part memoir, part travelogue, Tales From the Torrid Zone is a pleasing grab bag of a book, a jumble of funny encounters, strange sights, forgotten history and really bad food. Mr. Frater, a genial tour guide and a stylish writer, makes excellent company . . . [A] diverting tour of the earth’s hot zones.”

–William Grimes, The New York Times

“An outstanding memoir . . . Not everyone born and bred in the tropics likes tropical life. But just as church bells in the tropics have a unique resonance, so Frater himself has the human version of ‘tropical resonance.’ Everything about life in the tropics–food, diseases, insects, religion, rivers, language, drink, forestry, human sweat–is endlessly fascinating for him, reminding him of a story he heard traveling downstream from Mandalay, or filming in Mozambique, or riding a bus into Rarotonga. He finds the smallest details of tropical life so entertaining, he barely notices the attendant inconveniences. Thus he makes the insects eating his grandfather's book-selectively consuming its constituent parts, ‘the spine's sweet glue and crunchy muslin, biscuity strawboard covers, a confit of gold leaf licked from the titles’–sound like regular gourmands.”

–Publishers Weekly (starred)

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurPicador

- Date d'édition2005

- ISBN 10 0330375296

- ISBN 13 9780330375290

- ReliureBroché

- Nombre de pages400

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 269,13

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Tales from the Torrid Zone : Travels in the Deep Tropics

Edité par

Pan MacMillan

(2005)

ISBN 10 : 0330375296

ISBN 13 : 9780330375290

Neuf

Couverture souple

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Etat : New. . N° de réf. du vendeur 52GZZZ00BW4A_ns

Acheter neuf

EUR 269,13

Autre devise

Tales from the Torrid Zone : Travels in the Deep Tropics

Edité par

Pan MacMillan

(2005)

ISBN 10 : 0330375296

ISBN 13 : 9780330375290

Neuf

Couverture souple

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Etat : New. . N° de réf. du vendeur 5AUZZZ000B0H_ns

Acheter neuf

EUR 269,13

Autre devise