Articles liés à Tales of Two Cities: Stories of Inequality in a Divided...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNPENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

First published in the United States of America by OR Books 2014

Published in Penguin Books 2015

Copyright © 2014 by the various authors

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Illustrations by Molly Crabapple

Page 271 constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

ISBN 978-0-698-40830-2

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction · JOHN FREEMAN

Due North · GARNETTE CADOGAN

Options · DINAW MENGESTU

Every Night a Little Death · PATRICK RYAN

Miss Adele Amidst the Corsets · ZADIE SMITH

Near The Edge Of Darkness · COLUM MCCANN

The Children Suicides · MARIA VENEGAS

Partially Vacated · DW GIBSON

Four More Years · JONATHAN DEE

So Where Are We? · LAWRENCE JOSEPH

Round Trip · AKHIL SHARMA

Aliens of Extraordinary Ability · TAIYE SELASI

The Baffled Courtier: Lorenzo Da Ponte in America · EDMUND WHITE

Quid Pro Quo, Just As Easy As That · JEANNE THORNTON

Introduction · DAVE EGGERS

Park Slope Livin’ · CHAASADAHYAH JACKSON

One, Maybe Two Minutes from Fire · TÉA OBREHT

Service/Nonservice: How Bartenders See New Yorkers · ROSIE SCHAAP

A Block Divided Against Itself · SARAH JAFFE

Starting Out · JUNOT DIAZ

Engine · BILL CHENG

The Sixth Borough · JONATHAN SAFRAN FOER

Mixed Media, Dimensions Variable. · MICHAEL SALU

First Avenue & Second Street · HANNAH TINTI

Zapata Boulevard · VALERIA LUISELLI

Home · TIM FREEMAN

Introduction to Small Fates 1912 · TEJU COLE

Small Fates 1912 · TEJU COLE

Seeking · VICTOR LAVALLE

If the 1 Percent Stifles New York’s Creative Talent, I’m Out of Here · DAVID BYRNE

Traveling from Brooklyn · LYDIA DAVIS

Walt Whitman on Further Lane · MARK DOTY

Contributors

Acknowledgments

This book is for my brother Tim, who lives in both cities.

Introduction

JOHN FREEMAN

SEVERAL YEARS AGO, I bought an apartment in Manhattan with an inheritance passed to me from my grandmother, who was the daughter of a former attorney for Standard Oil. She outlived three husbands and managed her money well, and in one fell swoop from beyond the grave hoisted me out of one social class and into another.

Meanwhile, on the other side of town, my younger brother was living in a homeless shelter.

He was not far away—less than a mile. It was the second or third shelter he’d been in after moving to the city. It’s awkward enough, in most instances, to talk about money, but doubly so when it involves family. So let me just briefly say that my brother had not been left out of his inheritance; he just had no immediate access to it due to the fact that he has a mental illness. He has dealt with this illness bravely and takes precautions to manage his condition. One of the first things he did after moving to New York was check in at a hospital and use his Medicaid card to get his prescriptions.

Still, it was a very bad idea for him to move to the city. From afar, the decision felt like a car crash you watch in slow motion. We’d warned and pleaded, even begged him not to move to New York, my brother, father, and I did. My father told horror stories from when we lived here in the 1970s. I talked about how hard it could be just to sleep on some nights, with the heat, the noise, the city’s constant pulsing. My older brother talked to him about how difficult it was to find work, something my younger brother knew because he had been applying for jobs for over a year. Counselor, technological writer, librarian’s assistant, anything to do with words that paid better than minimum wage. He held a BA and had been published in newspapers.

None of that mattered in the end. He couldn’t get a job, and felt he couldn’t stay where he was—Utica—so he got on a train to New York and checked himself into a shelter. He had almost no belongings. He’d given them away or sold them. He brought a suitcase, a laptop he slept with so it wouldn’t be stolen, and a pay-as-you-go cell phone. These are luxuries in many parts of the world, but I assure you they were the thin string holding my brother’s life together by giving him a tenuous connection to the outside world, not to the one right around him. He kept us abreast of his movements by Facebook: which shelter he’d been kicked out of for fighting or calling people names, where he’d slept—the Staten Island Ferry, a bathroom at a bus station in Albany. Eventually, he wound up at this final shelter, and it was, to some degree, a last resort, where he lived for a while and joined their job-training program.

All the time that my brother was homeless, I never invited him over to where I lived or let him into my apartment. I love my brother. He can be sweet and very funny; he is gentle and kind to older people. Even when he made less than $10,000 a year, he spent hours each week tutoring and teaching people English. He is one of the most intelligent people I know, and every time I see him I am reminded how lucky I am to have him as a brother. I am also reminded how lucky I am that I was born, for reasons I cannot fathom, with a slightly different gene structure, one that means that I thrive under the same stress that makes his life impossible. It is not fair, but long ago I decided I would not spend my time trying to ameliorate the difference in our fortunes by fighting battles I knew are not winnable, among them trying to sort out his accommodation. I have had the experience of sharing a home with my brother and have arrived at the conclusion that it is better for us to live apart. During this time my girlfriend and I were contemplating conjoining our two adjacent apartments, and my feelings of guilt did not trump my resolve to avoid putting the relationship with my partner at risk from the strain of taking him in. I had seen the stress it had caused my parents. I knew my brother would be aware of the problems he was creating, and that it would be bad for him, too. At least that’s what I told myself.

So we communicated by Facebook and traded e-mails and once or twice met for lunch at a diner, where he arrived looking hollow and yet more alive than I had seen him in years. I almost didn’t recognize him. He had been walking everywhere and the food in the shelter was so bad, he’d lost forty pounds. He didn’t look sad anymore, but more like the brother I grew up with in California who was handsome and had girlfriends, a golden boy. He had much more energy now, too, as a result of being more fit, and deployed it wrangling the city’s social services bureaucracy. He had applied for a low-income housing program, and sent out resumes to jobs at the library. In the meantime, he was working up in Harlem, handing out free newspapers at the entrance to a subway. I realized in talking to him that to give him a lifeline to my house would have been a mistake; as hard as it was, he wanted to prove to us, and most important, to himself, that he could do this on his own. Still, I felt compelled to give him a few hundred dollars and he walked back into his life.

I couldn’t have predicted it then, but he succeeded. My brother got out of the shelter. He was accepted into the housing program, found an apartment, and, for a while, achieved his dream. He was living in New York, on his own. At first, he loved his new life. But as time went by, with his benefits package constantly under threat, he became increasingly tired of the strain of the city—the way it makes everything difficult, doubly so if you need help from it. Eventually he moved back to Utica and then on to Dallas, where he seems truly happy now. It’s warm, he has a car and things to do. He can live with a degree of peace and a lack of stress, and even if he has become a Republican, I still love him. I often like his photographs on Facebook.

I haven’t resolved how I feel about his time in New York. I don’t think I ever will, because the juxtaposition of our fates and fortunes is simply too much to assimilate. Too unequal. During the time he was here I rarely woke up later than 6:00 a.m. I was working for a British magazine and often had to travel to London for long periods. I was living there half-time, on and off airplanes on a monthly, sometimes weekly, basis and it messed up my internal clock. Meanwhile, he was living four blocks away in a shelter. On some mornings when I was in the city, I stood by the window of my apartment, drinking my first coffee while watching the dawn light up the walls surrounding the car park across the street. On some of those mornings he must have passed my building on his way from the shelter to the 1 train uptown to hand out newspapers, but he didn’t ring our doorbell. Did he even look up to see if I was there, worrying about him, wondering if he’d been kicked out his shelter after another fight? I asked him once why he never stopped by after he left the shelter and had an apartment of his own. He said, “It was cold, and I didn’t want to be late for work.”

· · ·

I TELL this story now because we need to change the way we talk about inequality. The reasons it exists are as complex as the reasons why my brother wound up in a shelter. Inequality is not an issue of us and them, the rich and the poor. You often see these same so-called divisions within one family, like mine. I have an instinct here to apologize for making this point, to add a caveat that my experience of witnessing my brother’s homelessness was not nearly as hard as it was for him to live it, while I’m sure there are people who have suffered far more than both of us. All this is true, I suppose, but it leads us into a cul-de-sac. To rank suffering creates a false hierarchy of pain, as if there were a way to compare and weigh grief with, say, physical discomfort, or career frustrations, or hopelessness. It allows us, to some degree, to say that some forms of suffering are OK while others are not.

City life is defined by proximity, and when people around city dwellers suffer, it creates stresses on everyone. Mayor Bill de Blasio was elected in part because his narrative of New York as a “Tale of Two Cities” struck a chord with people living in the city. He has called it “the central issue of our time.” New Yorkers related to his frustration and passion, his dream that the city could do much better. They were also, it’s fair to say, galvanized by the sense he conveyed in his campaign that the gap between the rich and poor, the haves and have-nots, has grown so wide as to make New York City untenable. The city’s narrative—of it being a special place, a city of dreams—shreds in the face of reality: the city’s income disparity is as big as it has ever been.

Some figures are necessary here in case you have not been following the news. Nearly half of New York is living near poverty, and in the last two decades the income disparity in the city has returned to what it was just before the Great Depression. The top 1 percent of New York earners saw their median income grow from $452,000 to $717,000 between 1990 and 2010. Meanwhile, the lowest 10 percent of New Yorkers saw a much smaller percentage growth, from just $8,500 in 1990 to $9,500 in 2010. The concentration of wealth in that period has also been remarkably skewed toward the very rich. In 1990, the top 10 percent of households earned 31 percent of the income made in New York; by 2010 that number had increased to 37 percent. And the very rich make up a large proportion of that group: in 2009, the top 1 percent earned more than a third of the city’s income. It is very clear. The rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer.

And the middle class, as it has been in the U.S. for some time, is progressively vanishing. Just prior to de Blasio’s election, James Surowiecki wrote a prescient column for the New Yorker outlining why this has happened. The city is highly dependent on the finance industry to create revenue—the top 1 percent pay a staggering 43 percent of the income tax—and yet that same industry is driving income inequality. Meantime, the kinds of jobs that bolster the middle class—manufacturing, for example—have vanished. Between 2001 and 2011 the city lost 51 percent of its manufacturing jobs. The cost of doing business in New York City, Surowiecki pointed out, is simply too expensive, and factories, workshops, and shipyards have gone elsewhere.

These numbers reflect an extreme version of what is happening in many U.S. cities, as people move back to urban areas from the suburbs, driving up urban home prices and rents. New York City has experienced that trend in an exaggerated way. New Yorkers who are not in the top 10 percent have seen just modest growth in their income, but they have faced catastrophic rent increases. Between 2002 and 2012, the median rent has risen 75 percent. Rent in New York City is now three times the national average. As a result, nearly one-third of New Yorkers pay more than 50 percent of their annual income in rent. Forget about not being able to afford to own; many New Yorkers cannot afford to rent. The New York City borough that spends the highest percentage on rent—the Bronx, where the typical household spends 66 percent of its income to rent a three-bedroom home—is also its poorest. Incidentally, this is where my brother lived once he got an apartment.

· · ·

These conditions are not sustainable. Moreover, the gap between what New York says it is—in its myths and pop culture, the images we retain of it when we visit, its literature—and its reality is not sustainable either. I would like it if this anthology could help to close the gap between the haves and have-nots in the city. It can perhaps do so by addressing this second gap, by thinking and dreaming and describing what it is like in New York City today. How does it feel, what does one see, what stories do we tell about ourselves, and how, if at all, has inequality changed the city?

In January 2014 I contacted a number of writers who live or have lived in New York City, who feel it is their home. Thirty of them responded. The anthology you have here is the result of their engagement with this issue, and their responses take many forms. There are memoirs and short stories, a collage, reported pieces, an essay on bartending, an urban travelogue, dispatches from housing court fights, an oral history, a poem, and even a Twitter series that turns headlines from 1912 into a kind of tone poem about violence and the city’s propensity to mulch its own.

Here is the city as it feels today, full of vanished bodegas and ghosts of a more mixed and various past. In Zadie Smith’s short story, an aging drag queen who has managed to hol...

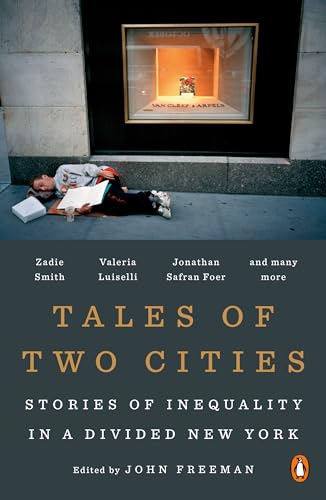

In a city where the top one percent earns more than a half-million dollars per year while twenty-five thousand children are homeless, public discourse about our entrenched and worsening wealth gap has never been more sorely needed. This remarkable anthology is the literary world’s response, with leading lights including Zadie Smith, Junot Díaz, and Lydia Davis bearing witness to the experience of ordinary New Yorkers in extraordinarily unequal circumstances. Through fiction and reportage, these writers convey the indignities and heartbreak, the callousness and solidarities, of living side by side with people of starkly different means. They shed light on the subterranean lives of homeless people who must find a bed in the city’s tunnels; the stresses that gentrification can bring to neighbors in a Brooklyn apartment block; the shenanigans of seriously alienated night-shift paralegals; the trials of a housing defendant standing up for tenants’ rights; and the humanity that survives in the midst of a deeply divided city. Tales of Two Cities is a brilliant, moving, and ultimately galvanizing clarion call for a city—and a nation—in crisis.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurPenguin Books

- Date d'édition2015

- ISBN 10 0143128302

- ISBN 13 9780143128304

- ReliurePaperback

- Nombre de pages288

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Tales of Two Cities: Stories of Inequality in a Divided New York

Description du livre Etat : New. . N° de réf. du vendeur 52GZZZ010Q64_ns

Tales of Two Cities: Stories of Inequality in a Divided New York

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Buy for Great customer experience. N° de réf. du vendeur GoldenDragon0143128302

Tales of Two Cities: Stories of Inequality in a Divided New York

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0143128302

Tales of Two Cities: The Best and Worst of Times in Today's New York

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : Brand New. reprint edition. 272 pages. 8.25x5.50x1.00 inches. In Stock. N° de réf. du vendeur zk0143128302

Tales of Two Cities: Stories of Inequality in a Divided New York

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover0143128302

Tales of Two Cities: Stories of Inequality in a Divided New York

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0143128302

Tales of Two Cities: Stories of Inequality in a Divided New York

Description du livre Etat : new. Reprint. Book is in NEW condition. Satisfaction Guaranteed! Fast Customer Service!!. N° de réf. du vendeur PSN0143128302

Tales of Two Cities: Stories of Inequality in a Divided New York

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. Brand New Copy. N° de réf. du vendeur BBB_new0143128302

Tales of Two Cities: Stories of Inequality in a Divided New York

Description du livre Paperback. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0143128302